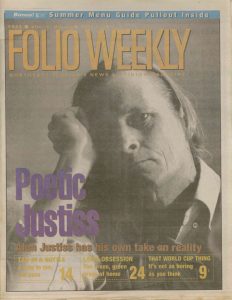

A Multidisciplinary Text Analysis Project Features the Poetry of Alan Justiss

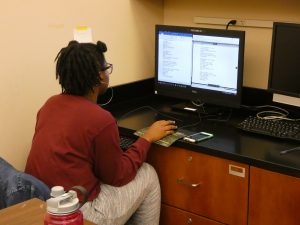

With the collaboration of Digital Scholarship Services and the support of a spring 2017 Digital Humanities in the Classroom grant, Professors Schettino and Gil are leading a text analysis project centered on the work of Alan Justiss, a poet based in Jacksonville, Florida, until his passing in 2011. Professor Gil was a close personal friend of Justiss’s; Gil now stewards Justiss’s physical archive, which consists of reams of type-written poetry in addition to photographic images, annotated calendars, chapbooks, and other ephemera. Student workers Julia Crawford ’19, Dilge Dilsiz ’19, KeeShawn Murphy ’20, and Ashley Zamichieli ’19 contribute to every stage of the project–from inventorying the physical materials (see image above), to digitizing the poetry archive, to creating machine-readable text-files of the poems using ABBYY FineReader Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software, to applying the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) software program for text analysis. Read on for an introduction to the project by faculty directors Schettino and Gil.

The poet Alan Justiss was active during the last few years of the 20th and the first decade of the 21st century, a period during which he was virtually always peripatetic, moving among friends’ houses and shelters without a permanent home. His writing habits were fascinating in the sense that they were very peculiar. Every night, if he had access to beer, he would sit down at his typewriter and produce poem after poem. Each poem was about one page long and written in blank verse. Interestingly, prior to the opening verse or title, Justiss would write, at the top of the page on the right margin, the date and number of each poem. As long as there was beer, poetry would flow. The following morning he would confide in friends whether the night had been good or bad, depending on the number of poems written. Upon his passing in 2011, Nestor set out to collect as many of the numerous typewritten pages as he was able to recover. The lot had been kept in a number of locations, wherever Justiss, in his wanderings, was able to store his output: garages, closets, storage sheds.

Dr. Luis Schettino, Associate Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience

Whether or not Justiss was a great poet, his immense output suggests he was a great writer of poetry. He seems to have preferred the freshness of language as it is produced. Or perhaps he enjoyed the act of writing more than the drudgery of careful revision. So he rarely made any modifications after pulling the sheet off the typewriter and stacking it neatly on the side. Some of his best work can be found in a few chapbooks, but by far, the bulk of his words sleep on thousands of yellowing paper sheets stored in plastic boxes.

Arts Associate KeeShawn Murphy ’20 analyzes digital images of Justiss’ s poetry

Our first move was to find a small group of exceptional students: exceptional in their abilities and in their endurance. Our second move was to ask these exceptional students to inventory the materials and organize the archive. It took the spring semester and summer break to catalog, count, and scan the texts. The total number of texts was 13,318, spanning the period from 1992 to 2010.

What can be accomplished with such a huge archive? How can this vast sequence of days and words afford us any sense in the artistic or scientific point of view? The key lies, we believe, in the notion of experience.

Alan Justiss left us a singular record of his experiences during those last 18 years of his life. His language, in the raw, is registered as patterns of word usage that can be analyzed using computational methods. Our goal is to identify and characterize those patterns in order to ask questions related to language production as a sensorimotor and cognitive process and questions related to the experience of a being using language to engage with others, but mostly with a personal notion of himself.

The project had a good start, but one important logistical step is still missing before we can unleash our computers on the corpus: turning the scanned images of Justiss’s work into analyzable text. Even though we have access to optical character recognition software, the process is far from straightforward. Our diligent students and we are hard at work correcting and ensuring the transcripts we have of each poem are of good quality. At our current rate, we estimate it will take at least a couple of years to transcribe every poem available. Nonetheless, interesting and useful results can be glimpsed by analyzing even relatively small samples of the large treasure trove Alan Justiss bequeathed us.